The cars that car designers drive

There would not be an artist from any time in history, or from any field of endeavour, who hasn’t taken inspiration from what’s gone before them.

The car designer is no exception.

And while the engineering under the bonnet needs to be the newest of the new, it’s the curves of the panels, the lines that draw the eye and the overall aesthetics that, in humble homage to the classics, often drives the design.

These four venerated Australian motoring designers each own a classic vehicle that has informed their work over the decades, and here they pay homage not just to the cars but also the designers who created these timeless beauties.

Paul Beranger

Paul began with GMH in 1968, working on the LJ Torana and designing the interior of the GTR-X coupe concept. He established and ran the Nissan Design Studio from 1977, created Nissan Special Vehicles Division a decade later in conjunction with Nissan Motorsport, and he was Toyota design manager from 2002 to 2012.

Paul Beranger first saw his dream machine at Mount Panorama, Bathurst, in 1969, when a De Tomaso Mangusta was driven round the circuit on a display lap.

“At around $12,000 back then it was a love affair way outside my league,” Paul reflects, “being about three times the cost of a Monaro GTS or Falcon GT. But I aspired to get one some day.”

Twenty years after that first sighting, Paul was finally able to buy one very tired Mangusta, then spent 15 years restoring it.

“There were precisely 401 Mangustas built in the late ’60s and early ’70s and this car is one of a handful built as right-hand drive,” he says. “It’s a raw car, ergonomically compromised – you need long arms and short legs.”

The car was an early design by Giorgetto Giugiaro, first seen as a prototype at the Turin Motor Show in 1966.

“The freshness and inspiration the young designer brought to creating a car for the Turin show is just as important to me as the car itself,” Paul says. “It symbolises how creativity can break through tired ideas of design.

“For its time, the windscreen is heavily raked; it’s almost a straight line from the front. Sharper angles clearly define where surfaces stop and start, giving the design a lot of movement and purpose.”

It’s a cosmopolitan car with Italian design, a Ford V8 engine and German ZF transaxle. As Paul notes: “It represents the point of change from front-engined to mid-engined two-seat sports cars.

“The strong body-wide line reduces the mass on the side of the car, while the use of light and shade makes the car look longer and leaner. I admire its purity and simplicity because design should stand alone without needing ornamentation.”

Phillip Zmood

Phillip started work with GMH in 1965. He led the design team for the HQ Monaro, ran the Torana design studio and designed the GTR-X concept coupe. In 1983, after heading the Opel design studio in Germany, he became the first Australian head of GMH Design. Fifteen years later, he became GM’s first director of design in China and was head of planning for the VE Commodore before retiring from GM in 2002.

In 1966, shortly after starting work with GMH, Phillip Zmood was sent to Detroit for special training in GM’s development program, working with its legendary head of design Bill Mitchell and star designers such as Larry Shinoda.

The car he drove most of the time in Michigan was a Series 2 Chevrolet Corvair Monza.

“I was attracted to the Corvair because it broke out of the mould of big American cars,” Phillip explains. “I loved its small size, its simple aesthetics, its rear engine. It was nippy and fun to drive and balanced the best European flavours with US manufacturing technology of that time.

“And while it was in the cheap car range, competing with the Volkswagen, Falcon and Valiant, it was advanced for its time. It was the first car with a flat-six engine, even before Porsche.

“The Series 2 combined high-end European looks reminiscent of design houses like Bertone with distinctive Chevrolet features such as the ‘Coke-bottle effect’, with a crease line along the waist and kick-up behind the door. The Corvair’s profile gives it wonderful balance between its roundness of shape and its line. The roofline and the pillars are in harmony and there’s not much superfluous stuff on it.

“The Series 2 combined high-end European looks reminiscent of design houses like Bertone with distinctive Chevrolet features such as the ‘Coke-bottle effect’, with a crease line along the waist and kick-up behind the door. The Corvair’s profile gives it wonderful balance between its roundness of shape and its line. The roofline and the pillars are in harmony and there’s not much superfluous stuff on it.

“I always wanted one after I returned to Australia in the 1960s. GMH brought a couple of Corvairs here to exhibit at motor shows but the car wasn’t sold here.

“In 1998, while I was working for GM in China, I’d have the local papers sent over to me. There was a 1965 Corvair Monza coupe advertised in The Age. When I rang my wife to ask her to get more details about the car, she told me the family had seen the ad and my son had just bought it for me.”

Peter Hughes

Peter began his career with Holden Design in 1990. He led the design team for the 2001 V2 Monaro and exterior design teams for the VE Commodore and new-generation Chevrolet Camaro. He is now the exteriors design manager for GM Australian Design.

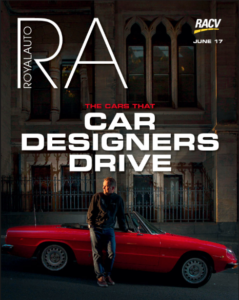

Peter Hughes has been an Alfa Romeo fan for as long as he can remember, and his 1750 Spider Veloce has been in his family most of his life.

Peter Hughes has been an Alfa Romeo fan for as long as he can remember, and his 1750 Spider Veloce has been in his family most of his life.

“I inherited my love of Alfas from my dad,” says Peter. “Before I was old enough to get my licence, I used to drive his 68 GTV coupe around the vacant block we owned next to our house.”

At Turin in the early 1960s, Alfa Romeo exhibited a series of show cars called Superflow, designed by Pininfarina, leading to the production Spider convertible, informally dubbed Duetto, in 1966. A revised Series 2 Spider followed in 1970.

“Dad brought home a brochure for the Duetto convertible soon after it was released,” Peter says. “With its rounded cigar shape I thought it looked like a spaceship. I was awe-struck.

“The 1971 model is one of the Series 2 cars that followed the Duetto. The earlier model was a push-me/pull-me type of design with equal overhang front and rear and a rounded boat-tail shape. The Series 2 has a square Kamm-tail design which I now think looks better than the Duetto. The chopped tail and more heavily raked windscreen gives it more speed, purpose and balance.”

Paul’s father bought his Spider as a wreck in 1977 and it sat under a tarp for years. “He gave it to me as a project for my 25th birthday in 1990.

Paul’s father bought his Spider as a wreck in 1977 and it sat under a tarp for years. “He gave it to me as a project for my 25th birthday in 1990.

“The Spider became the signature Alfa of the ’60s, with its side scallops and body curvature. The curves continue down the body sides, resulting in thick shapely doors, which was radical at that time.

“It’s a nice mixture of style and drivability that epitomises Alfa’s successful period. It’s a ’60s sports car; if you work to get the best out of it, then it rewards you.”

Michael Simcoe

Michael started work with GMH in 1983. He developed the flexible architecture design for multiple vehicles based on a single platform and designed the 1998 Commodore coupe concept which led to the reintroduction of the Monaro.  In April 2016, he became the first non-American to be appointed global head of GM Design.

In April 2016, he became the first non-American to be appointed global head of GM Design.

“I prefer a simple surface where the shape reflects light and supports the graphic elements like the grille, windows or tail lights,” he explains. “When people see the curves of this car they read the surface, so it’s more about surface and proportions than about graphics.

“It has a beautiful centreline profile and proportions, a short overhang with the four wheels close to the corners. It’s also beautiful to be in, with the interior as aesthetically efficient as the exterior.”

The Aurelia was the first Italian car to be called a GT and the first production car with a V6 engine. Racing drivers such as Juan Manuel Fangio chose the Aurelia as their road car.

“This particular car was built right-hand drive, like most Italian cars of its type were back then, even though they drove on the right hand side of the road,” Michael says. “There’s an apocryphal tale that it made it easier to see the precipice when you were driving on the edge of mountain roads.

“This particular car was built right-hand drive, like most Italian cars of its type were back then, even though they drove on the right hand side of the road,” Michael says. “There’s an apocryphal tale that it made it easier to see the precipice when you were driving on the edge of mountain roads.

“I love two-door cars, as they inevitably have a lower roofline and purer form. Designers start with a two-door profile. They can then apply it to a four-door car. Without the extra door a designer can do a lot more with the profile and surfacing. It becomes more sculptural rather than something dictated by doors and enables a smaller, more efficient design. The Aurelia represents the pure, unadorned two-door form.”

The art and science of car design

In the beginning, design wasn’t a major consideration for car makers or for their customers. Henry Ford is supposed to have been told by a farmer that what he needed most was “a faster horse”. Ford then went and supplied the Model T.

Early coach builders included some individual flair when constructing bodies that were bolted to the automobile chassis. But it wasn’t until Harley Earl established his Art and Colour Section at General Motors in 1927 that design began to find its place in the automotive world.

Melbourne’s Michael Simcoe took over as the head of global design at General Motors 12 months ago and moved into the office that Harley Earl occupied. “Car designers have always designed for a customer, to give emotional feedback,” Michael says.

“A car could be completely functional, but the designer’s job is to take engineers’ compromises and work with them to create an attractive design to reward the customer.

“Some car builders, like Ettore Bugatti, were both engineers and artists, but this is rare in the automotive industry. These functions have normally been separate, with engineers delivering function or capability, but designers are now bringing more engineering rigour than they used to, due to product safety legislation, integrated electronics and ergonomic considerations.

“As vehicles are engineered and manufactured much the same these days, the role of the designer is to be the difference between products. So if anything is stronger today, it’s designing for the customers’ needs, trying to give a mass-produced product as much individuality as possible.

“People have to be attracted by the exterior to engage with the car, and if the interior isn’t rewarding, easy to use, with intuitive operation of controls and functions like storage, people won’t come back. It’s applying art to science.”

Story: Tony Lupton

Photos: Shannon Morris

Published: RoyalAuto Magazine June 2017